Nuclear Regulation: By the Decade (1986–2000)

A modern regulator with comprehensive legislation – Enter the NSCA

Part 5 of a series on 70 years of nuclear safety in Canada: The coming into force of the NSCA and the creation of the CNSC

Where do you see the CNSC in 70 years?

“Legislation will continue to evolve and adapt to ensure that the CNSC has the authority it needs to fulfill its responsibilities over time and with changes. We can be confident that in another 70 years, Parliament will have ensured that the CNSC has the mandate and powers needed to do its job for Canadians, just as it has today in the NSCA.” –Lisa Thiele, Senior General Counsel and Director, Legal Services

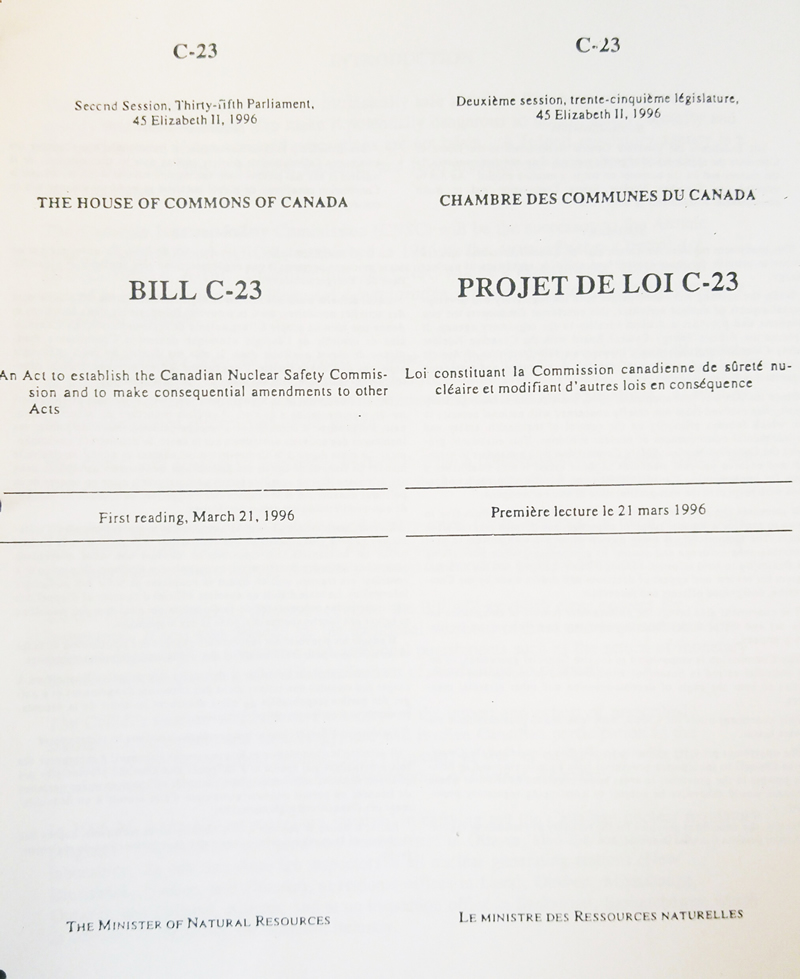

1996 was a notable year for nuclear safety in Canada. Not only was it the 50th anniversary of the Atomic Energy Control Act, but on March 21, 1996, the Hon. Anne McLellan, then Minister of Natural Resources, tabled Bill C-23 in the House of Commons, An act to establish the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission, and to make consequential amendments to other Acts. This would become the Nuclear Safety and Control Act (NSCA).

The Minister of Natural Resources tabled Bill C-23 in the House of Commons for the first reading, which would eventually establish the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission.

The new legislation was tabled to replace the Atomic Energy Control Act because, despite the dramatic changes in the size and the scope of the nuclear industry in Canada, the former legislation had never been significantly revised or updated in its 50 years. Members of Parliament said changes were long overdue as the focus of regulation was no longer the security of atomic secrets as it had been in the 1940s. Rather, the focus had become the health, safety and environmental impact of using nuclear technologies. Society’s expectations about how and why government should regulate the nuclear sector had also changed.

The NSCA addressed shortcomings of the former act by providing for more explicit regulation of nuclear activities and by ensuring that the regulatory body had the powers needed to fulfill its responsibilities. By explicitly referring to health, safety and protection of the environment, the new legislation clearly matched the Commission’s mandate to public expectations of its role.

Members of Parliament emphasized that Canada’s nuclear regulator must be, and must be seen to be, unbiased and neutral in its dealings with the nuclear industry. Dr. Agnes Bishop, then President of the Atomic Energy Control Board, took the opportunity when appearing before the Standing Committee on Natural Resources to stress the independence of the regulator in regulatory matters. Members stressed that it is equally important that the regulator be seen to be unbiased by both the public and the regulated industry.

The Committee held six weeks of hearings to gather opinions from a broad range of individuals and groups. It obtained a large amount of input which, by the third reading, was used to improve the bill. Many witnesses came forward to provide the Committee with opinions about the bill, and a number of changes were incorporated.

The bill was passed after third reading on February 18, 1997 and came into force on May 31, 2000.

Changes that came with the brand new CNSC

Like all new federal statutes, the NSCA was debated in the House of Commons.

The most notable change was the new name for the regulator, a name we now all use every day. A Member of Parliament explained to the House that the name change from Atomic Energy Control Board to Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission helped Canadians better identify with the Commission’s principal role and eliminated confusion with Atomic Energy of Canada Limited, which was the Crown corporation responsible for the development and support of CANDU nuclear reactors.

The NSCA differed from the former act in many ways, including greater enforcement power for individuals or corporations that contravened their licences, and the power to delegate administrative functions to the provinces where appropriate. It was clear that the Commission held more extensive powers in the licensing process, including the ability to hear witnesses, gather evidence and control its proceedings, as well as to call witnesses to hearings. The number of Commission members was increased from five to seven.

Based on information and extracts from the 1996–97 Hansard debates.

Page details

- Date modified: