Joint Audit and Evaluation of the Risk-Informed Compliance Verification Processes, Directorate of Power Reactor Regulation

Internal Audit, Evaluation and Ethics Division, February 2025

Executive Summary

The objective of this joint audit and evaluation engagement was to review the risk-informed compliance verification processes used across the directorates of the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC) in order to:

- provide reasonable assurance that the processes are systematic, well documented, objective, and incorporate consistency where applicable

- assess the performance and effectiveness of compliance verification delivery, provide insights on the achievement of expected outcomes and assess the soundness of performance measures

This engagement was conducted using a phased approach by directorate. This second phase covers the Directorate of Power Reactor Regulation (DPRR). Observations and recommendations in this report are tailored to DPRR.

Why this is important

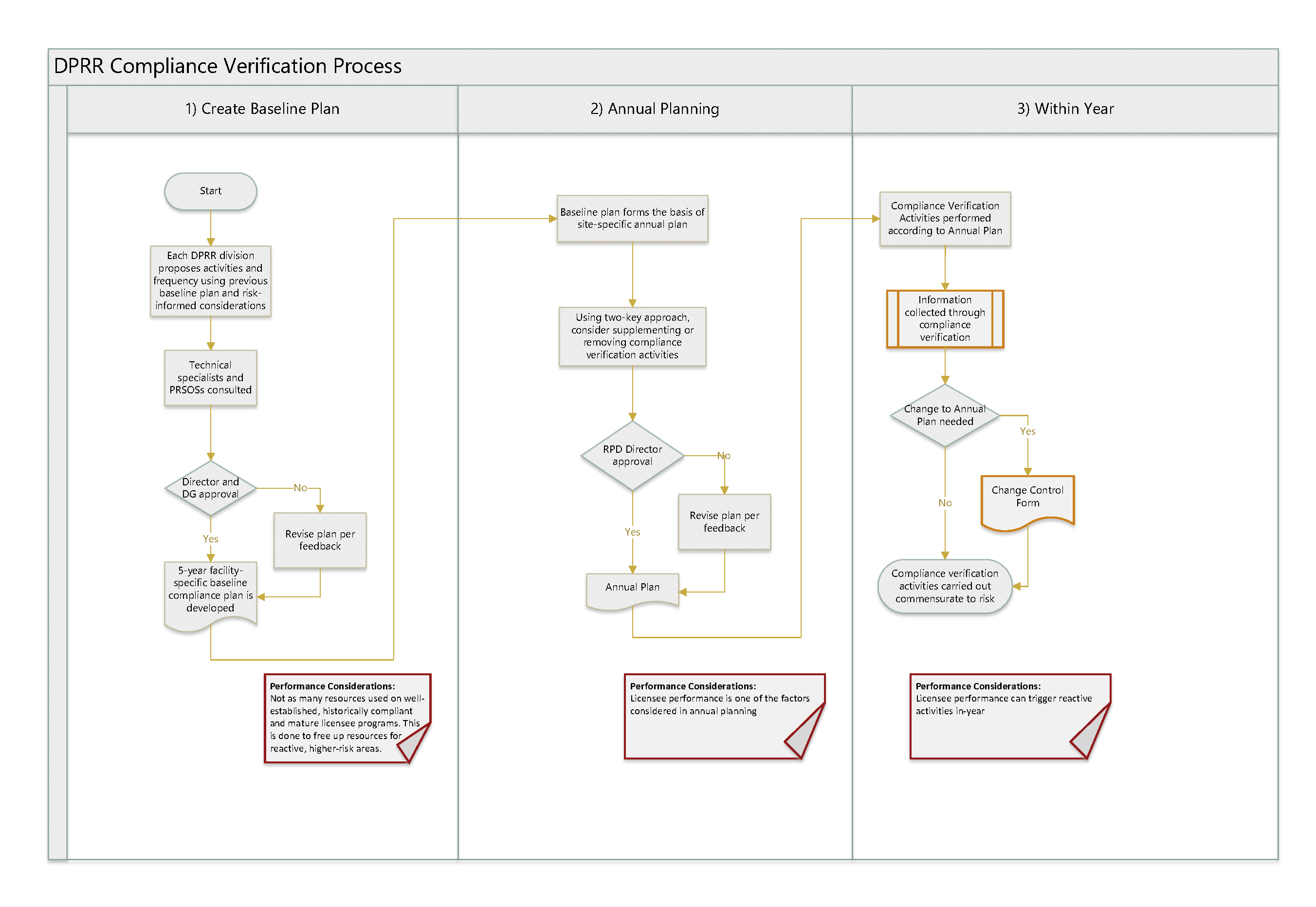

The CNSC’s compliance verification activities are in place to ensure that licensees are operating safely, securely, and in compliance with the requirements set out in the Nuclear Safety and Control Act (NSCA), its associated regulations, licences and certificates. These activities are guided, in part, by DPRR’s baseline compliance plan, which outlines the compliance verification activities to be completed over a 5-year period. This is validated annually as part of the annual compliance planning process.

It is imperative that the development of the baseline compliance plan, annual compliance plan, and other related activities use a risk-informed approach so that key risks are identified, monitored and adequately addressed to ensure that licensees are demonstrating a high level of compliance with the CNSC’s regulatory framework.

Key findings

The engagement found that DPRR had a comprehensive governance framework in place to ensure adequate oversight of risk-informed planning. The majority of the documented guidance reviewed was current and well understood by DPRR personnel. Risk-informed planning techniques deployed within DPRR were aligned with other benchmarked organizations, notably its recent updates to use more efficient methods of performing compliance verification and its approach to performing reactive and unannounced inspections. Tools and guidance were provided to DPRR personnel to support risk-informed inspection planning and the conduct of activities, and compliance verification plans were periodically reviewed to ensure relevancy and accuracy of risks. There was effective collaboration between DPRR personnel and other operations staff throughout compliance verification activities. Additionally, the performance of DPRR’s compliance verification inspections was consistently monitored against planned results and reported to management periodically, and an adequate process to manage the performance data related to activities.

Existing process documentation could be improved by including prompts that would trigger the need for unscheduled field checks. There is an opportunity to improve the annual compliance verification planning process by collaborating with the Operations Secretariat (Ops Sec) on the Operations Planning and Modernization Project. Information management (IM) can be enhanced by reducing inconsistencies and duplication with some IM tools used across divisions. There is an opportunity to enhance the existing performance indicator for baseline compliance verification activities by including CNSC-initiated assessments. Measuring these assessments, which are part of the baseline compliance verification plan, will help ensure that objectives are met and could identify areas for improvement. It appeared that the CNSC’s compliance verification program influences the safety culture of licensees, but opportunities for improvement have been identified by licensees that are worth exploring further, including the clarity of regulations and the compliance assessment process, and earlier notification of the compliance verification schedule.

This engagement includes 5 recommendations aimed at addressing the above-noted areas for improvement (see section 8). Management agrees with the recommendations, and its responses indicate its commitment to addressing them.

1. Background

The CNSC has a mandate under the NSCA to regulate the development, production and use of nuclear energy for all nuclear facilities and nuclear-related activities in Canada. To support this mandate, the Regulatory Operations Branch (ROB) and the Technical Support Branch (TSB) conduct compliance verification activities, such as inspections, to ensure that CNSC licensees exhibit a high level of compliance with the CNSC regulatory framework.

The CNSC authorizes the operation of 4 nuclear power plants (NPPs) – 3 in Ontario (Bruce, Darlington and Pickering) and 1 in New Brunswick (Point Lepreau) – by issuing licences that set out conditions designed to meet the requirements of the NSCA and its regulations. Licensees are responsible for ensuring the safe operation of NPPs. DPRR, which is part of ROB, supports the CNSC’s mission and mandate by providing leadership and expertise in the regulation of operating NPPs.

An inspection refers to a particular compliance verification activity conducted by various directorates in ROB and TSB, whereby information is gathered, analyzed and recorded for the purpose of evaluating whether a licensee activity is in compliance with regulatory requirements. A high-level overview of the inspection process is illustrated in Appendix B. Inspections are either planned or reactive. Reactive inspections can be triggered by desktop reviews, technical assessments or unplanned events, such as the occurrence of rare or unplanned regulated activities. Unannounced inspections, which are a type of reactive inspection, are those about which the licensee is not notified in advance, and they may be performed at any time. Reactive and unannounced inspections are conducted based on pre-established criteria, while ensuring that the entities subject to a reactive and unannounced inspection are aware of the inspection process, criteria and outcomes. For planned inspections, compliance plans are developed annually by each of the ROB directorates in cooperation with subject-matter experts (SMEs), most of whom are provided by TSB. TSB provides leadership and specialized expertise in various areas of nuclear science and engineering. See Appendix E for a description of the key compliance verification activities performed within DPRR.

The planning process ensures that compliance verification activities are planned in a systematic and risk-informed manner, known as risk-informed compliance verification (RICV). RICV considers key elements, such as regulatory requirements, licensee performance history, organizational considerations and the CNSC’s strategic outcomes.

Compliance plans outline the scope, scheduling, resourcing and time frame(s) for the verification activities to be undertaken for the next compliance cycle for a particular licensee. Compliance activities are guided by directorate-specific baseline plans, which are validated annually. Deviations from the baseline plans may be triggered by a variety of factors, including, but not limited to, inspections that were not completed during the previous year as planned, the recent performance history of the licensee, or significant upcoming changes to the licensee program.

In 2016, the Office of the Auditor General of Canada (OAG) examined whether the CNSC had adequately managed its site inspections of Canadian NPPs. One of the 5 audit recommendations was to develop and implement a well-documented planning process for site inspections of nuclear power plants that can demonstrate that the process is systematic and risk-informed. The CNSC President subsequently instructed all directorates that conduct licensee inspections to also address the OAG audit report recommendations as they related to their inspection programs. As a result, the CNSC refreshed its risk-informed approach to inspection planning between 2016 and 2020. A detailed timeline of related activities dating back to 2016 is outlined in Appendix C. The purpose of this joint audit and evaluation is to determine whether the risk-informed compliance verification processes used across the CNSC directorates are systematic, well documented, objective, effective and performing as intended.

2. Authority

This joint audit and evaluation is part of the CNSC’s approved Risk-Based Audit and Evaluation Plan for 2023–24 to 2024–25.

3. Objective, scope and approach

The audit objective was to provide reasonable assurance that the risk-informed compliance verification processes used across the CNSC directorates are systematic, well documented, objective, and incorporate consistency where applicable.

The evaluation objective was to assess the performance and effectiveness of compliance verification delivery, provide insights on the achievement of expected outcomes and assess the soundness of performance measures.

The engagement scope covered compliance verification activities in DPRR, including processes in place for developing risk-informed inspection plans, conducting risk-informed inspections as planned, and measuring the achievement of intended outcomes. The engagement scope covered the period from fiscal year 2021–22 to 2023–24, excluding the height of the pandemic (2020–21) when procedures were modified.

To complete the engagement, the following methods were used:

- Interviews with relevant stakeholders

- Documentation review

- Audit testing of completed compliance verification inspections

- Benchmarking against other nuclear regulators and federal government departments

- Survey of DPRR licensees

4. Statement of conformance

This engagement conforms with the Institute of Internal Auditors' International Standards for the Professional Practice of Internal Auditing and with Canadian Evaluation Society standards.

5. Acknowledgements

The engagement team would like to acknowledge and thank management and staff for their support throughout the conduct of this audit and evaluation.

6. Findings and Observations

6.1. Governance and Procedural Documentation

A governance framework is a set of rules and practices by which an organization ensures accountability and transparency with all of its stakeholders. A key component of an effective governance framework is well-defined and documented accountabilities. A clearly defined and integrated governance structure is key to ensuring program outcomes are achieved. The engagement expected to find a governance framework in place to ensure that roles and responsibilities are clearly defined and understood, with adequate oversight of risk-informed inspection planning.

Key findings

The engagement found that a comprehensive governance framework was in place, including defined responsibilities, accountabilities and oversight mechanisms.

There is an opportunity to enhance procedural documentation by incorporating prompts for unscheduled field checks.

6.1.1. Responsibility and Accountability

Roles and responsibilities were defined and documented, covering key activities to support the planning, execution, reporting and enforcement of DPRR’s compliance verification activities. Interviews with DPRR personnel demonstrated that responsibilities and accountabilities were clearly understood, and that oversight mechanisms were in place to ensure that compliance verification activities were reviewed and approved by management.

Responsibilities and accountabilities for key DPRR stakeholders, such as power reactor site inspectors (PRSIs), power reactor site office supervisors (PRSOSs), regulatory program officers (RPOs), regulatory program division (RPD) directors, and SMEs from TSB and ROB, were clearly documented in over 10 procedural documents, covering key activities such as:

- developing the 5-year baseline compliance verification plan

- developing the annual compliance verification plan

- performing Power Reactor Regulatory Program (PRRP) and field inspections

- performing site surveillance

- performing compliance assessments

Oversight mechanisms incorporated into DPRR’s compliance verification processes were well documented and understood by staff. Examples of oversight included RPD director review and approval of the site-specific annual compliance verification plan (ACVP), SME director review and approval of any SME recommendations made for the site-specific ACVP, and RPD director review and approval of compliance activity change request forms (CRFs) for any changes to the 5-year baseline compliance verification plan (CVP). Additionally, the PRRP established a quarterly review and integration meeting (QRIM) to review the progress of PRRP compliance verification activities. The QRIMs were chaired by the director of the Power Reactor Licensing and Compliance Integration Division (PRLCID) and consisted of permanent members at the director level from all divisions within DPRR and TSB, as well as several divisions from the Directorate of Nuclear Substance Regulation and the Directorate of Nuclear Cycle and Facilities Regulation (DNCFR) in ROB. Discussion topics included, but were not limited to, emerging trends, the risk significance of compliance findings, and decisions on future reactive activities. These examples were all consistent with the CNSC’s two-key system, which ensures that key stakeholders, such as PRSIs, RPOs, RPD directors and SMEs, are engaged heavily in making compliance verification decisions, thus providing a variety of perspectives on the files.

6.1.2 Documented Guidance – Completeness

The engagement team assessed whether procedural documentation was comprehensive. The assessment determined that a myriad of documents were in place to support the planning and conduct of DPRR’s compliance verification activities.

Reactive compliance verification activities were well defined and documented in the FY2023–28 Power Reactor Regulatory Program Baseline Compliance Verification Plan. For example, the guidance indicated that reactive compliance verification activities can be added outside the annual planning period to react to emerging issues, findings from baseline compliance verification activities, unscheduled licensee submissions and recommendations from compliance assessments. Through interviews with DPRR personnel, it was evident that the procedure for adding reactive compliance verification activities was clearly understood.

Steps for adding or removing compliance verification activities in the site-specific ACVP were integrated into the work instructions for developing the ACVP. Key steps include consultation with other stakeholders and completion of the compliance activity CRF. Information on what could prompt changes to the ACVP, including deferrals, cancellations or reactive activities, are documented separately in the compliance activity CRF.

The work instruction for performing site surveillance (e-Doc 3678787) outlined the steps for executing unscheduled field checks, which were consistent with what was described by DPRR personnel. To promote greater clarity and understanding, it would be beneficial to update the work instruction with prompts that would trigger the need for an unscheduled field check. The prompts are meant to provide guidance to staff, who should take the prompts into consideration in addition to using their judgment.

6.1.3 Conclusion

DPRR’s risk-informed compliance verification processes were supported by a comprehensive governance framework with defined responsibilities, accountabilities and oversight mechanisms. Documented guidance was in place describing key steps for supporting the planning, execution, reporting and enforcement of DPRR’s compliance verification activities. Guidance on reactive inspections was well documented, and DPRR personnel demonstrated a strong awareness and understanding of the process for initiating a reactive inspection or other change to the annual or baseline compliance verification plan using the CRFs. There is an opportunity to enhance the procedural documentation by including prompts on when an unscheduled field check may be triggered.

Recommendation

- DPRR should update the document How to: Perform Site Surveillance to include triggers for an unscheduled field check.

6.2 Risk Management

Risk management refers to the identification and evaluation of risks to organizational objectives. The engagement expected to find a systematic process used to identify, evaluate and prioritize risks to support the planning and conduct of compliance verification activities at the CNSC.

Key findings

The engagement found that DPRR’s compliance verification activities were periodically reviewed to ensure the relevance and accuracy of risks.

DPRR’s risk-informed planning practices were aligned with best practices identified at other international regulators, notably its recent updates to use more efficient methods of performing compliance verification and its approach to performing reactive and unannounced inspections.

Resourcing has been identified as a risk at the CNSC owing to an anticipated increase in regulatory activities and ongoing competition for skilled staff in the nuclear industry. DPRR has proactively assessed the impacts and has taken appropriate steps to seek approval to resource its future anticipated needs, including for the Darlington New Nuclear Project (DNNP) and the refurbishment of Pickering Nuclear Generating Station Units 5 to 8. Additionally, low turnover of management positions within DPRR was observed throughout the engagement.

6.2.1. Relevance and Accuracy of Risks

The engagement found that DPRR’s compliance verification activities were periodically reviewed to ensure the relevance and accuracy of risks. Processes were in place to review risks in baseline, annual and in-year planning.

Prior to developing the 2023–28 baseline compliance verification plan, DPRR launched the PRRP Oversight Productivity Project (PROP). The PROP’s vision was “to bring together multidisciplinary teams to identify agile and effective improvements”. The goal was to perform compliance activities in a “timely, responsive, efficient, effective and risk-informed manner to maximize the quality of the outputs from the currently available compliance resources”. The PROP focused on 5 improvement areas, including the Baseline to Requirements (B2R) project. The mandate of the B2R project was “alignment of approved baseline compliance activities linked to the regulatory requirements to determine and ensure that each Safety and Control Area (SCA) has systematic coverage at the necessary frequency”.

As part of the documentation review, the engagement team examined working-level documents from the B2R project. These documents demonstrated an in-depth analysis of compliance activities completed, where duplication of effort might exist and where there may be room for efficiencies in the 2023–28 baseline plan, while still providing sufficient risk coverage.

The results of the B2R project were leveraged when developing the 2023–28 baseline compliance verification plan. DPRR implemented measures to reduce duplication of effort in compliance verification activities, while still providing adequate baseline risk coverage. This included greater focus on sampling of the licensee program, which should require fewer routine in-depth inspections, and using more efficient methods of performing compliance verification, such as field inspections for routine field checks previously executed through Type II inspections. The intent of this initiative was to free up resources in order to react in-year to high-risk areas of concern. This initiative aligned with best practices identified by the Internal Audit, Evaluation and Ethics Division (IAEED) in international benchmarking.

The engagement team conducted a benchmarking exercise with other federal departments and international nuclear regulators, as outlined in Appendix D. Through benchmarking, it was found that other federal government departments deploy distinctive models to establish systematic risk-ranking processes in their organizations. Each risk model considered factors that were specific to each of the regulated parties, rather than applying a generic approach (refer to figure 1 for details).

Figure 1: Risk identification practices of other Canadian federal government departments

- One department had a science-based risk model that drives its inspection plan, focusing on 3 key elements: inherent risk, regulatory control requirements, and the compliance history of the establishment.

- One department had a risk model that assesses the risks or potential consequences for all of the regulated organizations it evaluates, using a tailored approach for each organization. Risk factors included product or service provided, related hazard, and proximity of the potential hazard to people, water, habitat and so on.

- One department generally applied a numeric scale (usually from 1 to 5) to represent the degree of perceived risk within the targeted entity. Some programs used advanced machine-learning algorithms to generate their rankings, while others relied on expert opinion and judgment.

- One department deployed risk profiling to inform inspection prioritization using data collected from previous inspections, licensing applications and international partners. Various factors are taken into consideration when risk profiling a site, with the profiles differing based on factors such as location and compliance history.

Similarly, all international nuclear regulators used a risk-informed inspection process, whereby the level of regulatory attention applied to the licensee is based on multiple factors, such as the level of hazard and risk posed by the facility or activity, and the licensee’s history of safety and security. All of these assessments were underpinned by qualitative and quantitative measures, such as the number and significance of regulatory issues and the number and significance of incidents, gathered through regulatory activities. Additional risk identification practices deployed by international regulators are highlighted in figure 2. These principles are aligned with DPRR, notably the first point, which focuses on the efficient use of resources and sampling to ensure that areas of greater risk are targeted.

Figure 2: Risk identification practices of other international nuclear regulators

- One regulator moved away from reviewing everything on a periodic basis in 2018 to promote the efficient use of resources, especially for low-risk areas. The regulator now uses a risk- and intelligence-based review, consisting of risk-informed sampling to ensure that areas of greater risk and areas of least control are targeted, rather than reviewing everything periodically.

- Two regulators used a sampling approach rather than 100% inspection. This sampling approach was informed by risk and with the underlying premise that the licensee is responsible for controlling hazards and risks associated with its undertakings.

- One regulator used 3 levels of regulatory attention: routine, enhanced and significantly enhanced.

- One regulator applied the principle of proportionality when determining its actions, so that the scope, conditions and extent of its regulatory actions were commensurate with the human and environmental protection implications involved.

- One regulator stated that regulatory oversight is informed by the complexity and potential harm posed by the licensed activity or facility. This means that those posing lower risk will be subject to less oversight and scrutiny.

6.2.2. Reactive Inspections

Reactive inspections were clearly defined in DPRR’s FY2023–28 Power Reactor Regulatory Program Baseline Compliance Verification Plan, with examples of relevant triggers. Through interviews with DPRR personnel, it was evident that the process for initiating reactive inspections was well understood. DPRR personnel indicated that reactive inspections were typically added to the plan based on insights from DPRR's surveillance and monitoring activities, which were tracked in site-office data repositories (SODRs). Based on a documentation review, the engagement team confirmed that insights were consistently tracked across the 4 site offices using site-specific SODRs. There was an understanding among DPRR personnel that if reactive inspections were added in-year, a CRF had to be completed to provide justification. The engagement team found that triggers for reactive inspections vary; however, the process for initiating a reactive inspection and documenting the rationale was consistently applied through the use of CRFs.

The engagement team conducted a benchmarking exercise against other international nuclear regulators and Canadian federal government departments. The benchmarking exercise found that the use of reactive inspections is common among all participants, including the CNSC. For some participants, the number of reactive inspections conducted was contingent upon associated risk, while for other participants, a prescribed percentage of resources was allocated for reactive inspections during planning. For example, one federal government department indicated that 15% of its plan was allocated for reactive inspections, while one of the international regulators indicated a 5% allocation. Additionally, one federal government department noted that when a reactive inspection was triggered by a complaint, it often conducted an unannounced onsite compliance inspection, as it was most likely to get a true assessment of day-to-day operations.

Anticipating reactive inspections in advance may reduce the risk of high workloads among staff, while ensuring that sufficient capacity is available for unexpected events as needed. This practice was recently implemented by DPRR. According to DPRR personnel, the number of planned baseline inspections was reduced to allow more room and flexibility for reactive work. Feedback from some DPRR personnel noted that this change has made their workloads more manageable.

6.2.3. Unannounced Inspections

According to DPRR personnel, unannounced compliance verification activities may occur as part of field inspections. PRSIs have full access to the station and licensee databases and may choose to verify elements not on the field inspection plan. This unfettered access allows PRSIs to conduct field walkdowns without informing the licensee. These walkdowns are conducted regularly as part of DPRR’s surveillance and monitoring activities, particularly if something unusual is observed.

The benchmarking exercise revealed that all benchmarking participants performed unannounced inspections. Two of the 4 Government of Canada departments that conducted unannounced inspections generally did so in response to a trigger, such as a complaint or an issue observed during an inspection. Refer to figure 3 for additional details.

Benchmarking participants and DPRR personnel noted that unannounced inspections can provide a more complete picture of a situation at a facility, allow the regulator to maintain its authority status by keeping the licensee aware that the regulator can come in at any time, prevent the licensee from managing its workplan according to announced compliance verification activities, and increase the likelihood of getting a true assessment of day-to-day operations by foregoing advance notice to the licensee.

Figure 3: Unannounced inspections by other Canadian federal government departments and international nuclear regulators

- Two international nuclear regulators performed unannounced inspections in response to a trigger (e.g., whistleblower information). One Canadian federal department often conducted unannounced inspections in response to complaints.

- One international nuclear regulator conducted unannounced inspections only on nuclear power plants.

- One international nuclear regulator routinely conducted unannounced activities. To improve the efficiency of inspection trips and to reduce agency costs, it may contact the licensee on short notice to verify that the inspection can be performed at the intended time.

- One Canadian federal department conducted unannounced inspections on an ad-hoc basis if an inspector was in the vicinity of a potential issue. Additionally, random unannounced inspections were practiced by some programs in this department for quality control of the risk-based program.

- One Canadian federal department noted that unannounced inspections can be done in response to a concern or complaint. The preference of this department was to avoid them in order to ensure that the regulated party had the available staff and paperwork available at the time of the inspection.

- One Canadian federal department conducted some unannounced inspections on an infrequent basis.

6.2.4. Planning and Resource Capacity

Electricity Human Resources Canada is a leading provider of human resources data and trends within the Canadian electricity industry. In its latest publication, Electricity in Demand: Labour Market Insights 2023–2028, acquiring skilled talent was identified as the most pressing constraint for Canada’s electricity sector over the next 5 years Footnote 1. Given the rise of emerging technologies, such as small modular reactors, and the CNSC’s expanding mandate, it is important to be mindful of this constraint when planning DPRR’s activities. This consideration is pertinent to DPRR’s involvement in the DNNP and Pickering refurbishment as these projects will require specialized resources over time to carry out the CNSC’s mandate.

CNSC staff have engaged in various readiness activities in anticipation of the increased workload. This included the development of a DNNP licence-to-construct compliance verification plan that identified activities that will be led by DPRR staff. The plan considered several inputs, such as operating experience in regulatory oversight during construction, review of regulatory and International Atomic Energy Agency documentation, ranking of relevant SCAs according to risk, and discussion with key stakeholders. Resource allocation for inspectors, RPOs and SMEs was identified as a project constraint, and resourcing has been identified as a risk throughout the CNSC. Based on a review of estimated compliance activities, an initial number of inspector full-time equivalents (FTEs) was calculated. These details informed the business case that was developed in October 2024 to ensure that the CNSC had adequate resources to conduct the expected regulatory work for the DNNP. The business case outlined a requirement for additional FTEs and was approved by the Integrated Planning and Resource Management Committee.

The CNSC is also assessing a periodic safety review of the refurbishment of the Pickering Nuclear Generating Station Units 5 to 8 (PSR3) to support long-term operations of the Pickering NPP. This is another initiative that will require DPRR resources. The PSR3 assessment has an approved project plan that sets out the purpose, scope, deliverables, project team, key risks and estimated resourcing efforts for the next 3 fiscal years. The estimated efforts and resources for the CNSC’s oversight and compliance verification activities are documented in the PSR3 project plan. According to management, these estimates are based on the previous Pickering and Darlington PSR efforts and are incorporated into the planning every year. Management indicated that the CNSC’s review of the PSR3 might not impact the overall CNSC resources. However, there might be some reprioritizing across the CNSC in some directorates to support the review of the PSR3.

It is evident that the annual planning process helped to estimate the level of effort required to carry out compliance verification activities. Most PRSIs that were interviewed expressed that the workload from compliance verification activities is high, but overall achievable. There was general consensus among the PRSIs that the workloads are appropriate, especially when the site offices are fully staffed. It was also indicated that the newly modified baseline plan with fewer planned inspections has helped improve workloads and has allowed staff to target riskier areas through increased reactive inspections. However, workload capacity was raised as a challenge in interviews with RPOs. RPOs indicated that workloads were generally high owing to competing priorities and their other duties, which included occasionally training and mentoring replacement staff. This observation is consistent with what was shared by directors in engagement interviews. All directors agreed that the constant movement of staff within the CNSC had an impact on workloads. Some directors expressed that the burden falls on the shoulders of senior staff through having to train new people. Measures to address high workloads were also noted, such as deferring an activity through the change request process, prioritizing activities from the baseline plan, and working extra hours. Although RPO effort is not a significant component of compliance verification activities, this broader challenge should continue to be a discussion for identifying mitigating strategies.

Resourcing has been identified as a risk at the CNSC owing to an anticipated increased demand for regulatory activities and ongoing competition for skilled staff in the nuclear industry. These factors have a direct impact on DPPR in terms of its expected regulatory work for the DNNP and the Pickering extended operation. It is important that DPRR’s capacity requirements to carry out its mandate continue to be monitored and assessed throughout its planning activities.

6.2.5. Conclusion

DPRR’s compliance verification activities were periodically reviewed to ensure the relevancy and accuracy of risks. Risk identification practices deployed in DPRR were aligned with the results of the benchmarking exercise, notably DPRR’s efforts to use resources more efficiently.

A well-defined process was in place to initiate changes to compliance verification plans in-year through the change request process, which was consistently applied by DPRR personnel. Similar to the benchmarked organizations, reactive and unannounced inspections were conducted in DPRR, and the benefits were well understood by staff.

With the anticipated expansion of DPRR’s regulatory work and the ongoing competition for skilled staff, it is crucial to regularly monitor and adjust the assumptions in the DNNP and PSR3 project plans as needs change or assumptions do not materialize.

6.3 Planning and Conduct of Inspections

The engagement expected to find mechanisms in place, including periodic reviews of the inspection plan and documented guidance to support staff, in order to ensure that the planning and conduct of inspections are consistent with the associated levels of risk.

Key findings

The engagement found that DPRR’s compliance verification activities used a risk-informed approach and considered relevant factors, such as licensee performance and resourcing, when prioritizing and planning inspections.

There is an opportunity to streamline the annual compliance verification planning process to ensure that DPRR personnel are notified of planned activities earlier in the year, which may allow more flexibility in carrying out their activities. There is an operational planning improvement project underway led by Ops Sec that may address this opportunity.

Tools and guidance were provided to DPRR personnel to support risk-informed inspection planning and the conduct of activities. The consensus among DPRR staff was that these tools were adequate to meet their needs.

Audit testing confirmed that DPRR’s completed inspections were consistent with established plans, priorities and risks and that they complied with DPRR procedures.

6.3.1. Planning Risk-Informed Inspections

Interviews and a documentation review demonstrated that DPRR’s compliance verification activities used a risk-informed approach and considered relevant factors such as licensee performance, resourcing and emerging technologies when prioritizing and planning inspections. Risk-informed compliance verification planning in DPRR starts with a 5-year baseline plan that serves as the basis for the site-specific annual CVP developed for each of the site offices.

The 2018–23 PRRP baseline CVP indicated that there were 6 risk-informed considerations to be applied when developing the baseline CVP. These criteria were regulatory requirements; deterministic considerations; probabilistic considerations; organizational considerations; licensee performance history; and other considerations such as operating experience, periodic safety review and engineering/technical judgment. According to management, these factors were considered when prioritizing activities for the 2018–23 baseline CVP. The 2018–23 baseline plan in turn was the starting point for the 2023–28 baseline plan. The team working on the changes to the 2023–28 baseline plan proposed which Type II Footnote 2 inspections could be replaced by field inspections or compliance assessments for the new 5-year baseline CVP. This proposal was based on a number of factors, such as considerations for programs reviewed by the CNSC as part of licensing, status of notification requirements for program changes, types of verifications in the inspection guides (including overlap with other compliance oversight activities) and licensee performance. The analysis to support this proposal was documented in an efficiency review of existing inspection activities performed and was considered in the modification of the baseline CVP for 2023–28.

In addition, the work instruction for developing the site-specific annual CVP indicated that PRSOSs were to provide input on prioritizing the number and types of activities that should be selected for the annual compliance verification plan, taking into account site resources. An interview with a PRSOS confirmed that they were given the opportunity to provide input and that reactive or supplemental inspections were added and prioritized based on criteria such as licensee performance or regulatory requirement changes.

DPRR personnel identified a challenge pertaining to the length of the annual planning process. Through interviews with DPRR personnel, it was noted that the annual compliance verification planning process took approximately 5 to 6 months, and in some cases, resulted in a long wait before a final approved plan was distributed. DPRR personnel indicated that earlier notification would be helpful to allow more room for planning. DPRR management agreed that annual compliance verification planning is extensive and resource intensive, and that it could benefit from efficiencies to streamline the process. DPRR management also confirmed that staff are notified of the planned compliance verification activities before the final approved plan is circulated each year and that they have the flexibility to plan their work ahead of time if needed. It would be advantageous for management to reiterate this message to DPRR personnel to ensure that there are no delays in the planning or execution of scheduled compliance verification activities. It is worth noting that the CNSC is currently engaged in the Operations Planning and Modernization Project that is being led by Ops Sec. The intent of the project is to review how the organization conducts the annual operations planning process and identify ways it can be improved, including through multi-year planning. This presents an opportunity for DPRR to participate in the project to ensure that efforts are not duplicated and that improvements are implemented consistently.

In examining compliance verification planning through the benchmarking exercise, the results demonstrated that all international regulators included risk as a key component of their planning. Similar to the CNSC, the regulators prepared a long-term plan and corresponding annual plan. The long-term plan sets out the entire suite of activities to be performed over a multi-year period, with the annual plan setting out in detail the activities to be performed each year.

6.3.2. Conducting Risk-Informed Inspections

The engagement team used non-statistical sampling to select a sample of 31 completed inspections from fiscal year 2023–24. Using professional judgment, inspections were selected from across DPRR that varied by inspection type and by SCA, and included a balance of scheduled and unscheduled (reactive and Type I) inspections. Footnote 3 The engagement found that DPRR’s inspections were consistent with the CNSC’s established plans, priorities and risks and DPRR’s internal procedures.

The audit testing demonstrated that all of the scheduled inspections from the audit sample were included in the 2023–28 PRRP baseline CVP and aligned with key risks in the CNSC’s Departmental Plan in relation to nuclear reactors. It was also found that all of the sampled inspections were completed in accordance with DPRR’s internal procedures. For example, key requirements to assess and document the safety significance of inspection findings in an inspection memo, document the record of observations using the appropriate tool, and obtain director sign-off on the inspection cover letter were all completed as required.

6.3.3. Supporting Templates and Guidance

A wide range of process documentation and templates is available within DPRR to support the planning and conduct of compliance verification activities. Examples include work instructions for developing the site-specific annual CVP, performing PRRP inspections and performing compliance assessments.

The work instructions also referenced different tools and templates available to support the planning and conduct of risk-informed compliance verification activities. For example, the work instruction on developing the site-specific annual CVP included references to several planning templates, such as the compliance activity CRF, the CVP effort planning template, and the compliance activity change tracking tool. As another example, the work instructions for performing PRRP inspections contained references to various templates to support the conduct of inspections, some of which included templates for inspection plans, notification letters, inspection schedules, observation forms and inspection reports.

The consensus among DPRR personnel was that sufficient tools and guidance were in place to support the planning and conduct of DPRR’s risk-informed compliance verification activities and that these tools and guidance were adequate to meet their needs.

6.3.4. Review and Approval Processes

The engagement team found that DPRR’s compliance verification activities incorporated sufficient review and approval processes. For example, the site-specific ACVP required review and approvals at the director level. For any SME recommendations made to the site-specific ACVP, the respective SME director’s review and approval was also required.

The engagement team also found that a defined process was in place for modifying compliance verification plans. Process oversight was ensured by submitting a completed CRF. The form outlined the type of change requested (deferral, cancellation, adding/subtracting an activity), the SCA concerned, and risk considerations. Furthermore, there was a section for required signatures for approval. Interviews with DPRR personnel demonstrated an awareness of CRFs as the appropriate means for modifying the risk-informed CVP. It was also understood by interviewed personnel that the review and approval process was established and managed by PRLCID.

To assess compliance with the CRF process, the engagement team tested a sample of CRFs to determine whether they were completed according to DPRR’s documented work instructions. It was found that all CRFs tested contained a rationale for the requested change and linked the change to the pertinent regulatory requirements. In addition, almost all of the tested CRFs included text on the safety significance of the change and included the required approvals. These results are consistent with the results of reactive inspections tested from the audit sample. For a majority of the reactive inspections tested, CRFs were consistently completed, approved, saved and tracked in a spreadsheet. Some reactive inspections from the sample did not have corresponding CRFs. According to PRLCID, there are some situations in which this is acceptable. For example, an inspector may deem that a reactive inspection is necessary in response to an event, without sufficient time to raise a CRF. PRLCID indicated that this is within the roles and responsibilities of designated inspectors, and DPRR administrative processes are not intended to prevent or delay necessary compliance verification activities. In such a situation, a CRF is ideally completed after the fact as an administrative step but is not necessary as there is no decision to be made. The 2 exceptions from the audit sample fell into this category.

6.3.5. Conclusion

The engagement found that DPRR staff were well-informed of the documented guidance in place to support risk-informed compliance verification planning and conduct. Templates and guidance were provided to DPRR staff to support risk-informed inspection activities, and evidence demonstrated that they are used to complete inspections. Additionally, audit testing confirmed that DPRR’s completed inspections were consistent with established plans, priorities and risks and complied with DPRR procedures. The safety significance of findings was systematically assessed and documented in writing in the inspection memo. Inspection information was well documented, accessible, accurate and consistent among the various tools used.

There is an opportunity to emphasize and consistently use the draft annual compliance verification plan to ensure that DPRR personnel are notified of planned activities earlier in the year, which may reduce the burden on staff and allow more time to carry out compliance inspection activities.

Recommendation

-

DPRR should take steps to improve the annual compliance verification planning process:

- DPRR should document and communicate to staff that the draft annual compliance verification plan should be used to prepare and initiate planned activities earlier in the year.

- In collaboration with Ops Sec, DPRR should participate in the Operations Planning and Modernization Project to ensure that efforts are not duplicated and that DPRR requirements are met.

6.4 Operations, Information and Knowledge Management

Operations management is the administration of business practices to build efficiency within an organization. Footnote 4 Information management Footnote 5 and knowledge management Footnote 6 serve to identify, collect, store and disseminate information to harness collective knowledge within an organization. The engagement expected to see a formal approach to information and knowledge management to promote the effectiveness and business continuity of DPRR’s compliance verification activities. This includes the consistent use of IM tools that deliver accessible, reliable and accurate information, and effective collaboration within the directorate.

Key findings

The engagement found that corporate IM systems are used fairly consistently and that the use of the online document repository for all approved governance was viewed as a best practice. There are opportunities to better integrate current IM tools to reduce duplicative efforts.

Audit testing demonstrated that the use of IM tools was well understood by DPRR personnel, and that information related to completed inspections was well documented and accessible.

As the organization onboards the new MS365 tools and implements the CNSC Digital Strategy, there is an opportunity to assess and potentially optimize efficiencies and integrate processes for compliance verification activities.

There was effective collaboration between DPRR personnel and other operations staff throughout the inspection process.

6.4.1. Information Management Tools

DPRR personnel used a variety of digital tools for the purposes of information management. Figure 4 identifies the main tools used across the CNSC and provides a description of general use within DPRR. Some of these tools, such as the Case Management System (CMS) and the Regulatory Information Bank (RIB), were more rigidly designed and provide an audit trail. Other tools, such as the Microsoft Office suite, are flexible and fit for purpose.

Figure 4: IT tools for DPRR compliance verification activities

| IT tool | Use by DPRR staff |

|---|---|

| Case Management System (CMS) | Used as a repository for inspection information and related data |

| Regulatory Information Bank (RIB) | Used by RPOs for several purposes, such as tracking actions stemming from inspection reports, tracking correspondence and conducting compliance assessments |

| Job Management System (JMS) | This is an SME-driven tool to assign tasks to lead divisions with a proposed completion date to ensure that work will be done in a timely manner |

| Central Event Reporting and Tracking System (CERTS) | A database to report and track all NPP-reported events submitted by licensees |

| Online document repository | Used to store and access process documents, tools and templates via an online cloud platform |

| e-Access | Used as a filing repository to securely organize and manage work documents on the CNSC network |

| Spreadsheets | Used internally across divisions to plan and track various items, such as change request forms and insights from surveillance and monitoring |

| Word documents | Used to write key documents such as reports |

| Dashboards | Used to track progress against the compliance verification plan and for monitoring purposes |

In DPRR, an online document repository was leveraged to provide staff with easy access to all DPRR approved process documentation. This was identified as a best practice among DPRR personnel and was noted as a common strength of the IM tools overall. The repository is a cloud-based platform used within DPRR to store and organize its process documentation in one place, keeping all staff aligned on the most up-to-date information. It includes a wide range of process documentation and templates to support the planning and conduct of compliance verification activities. The documentation is categorized by function (e.g., compliance), with sub-categories for each of the function’s activities (e.g., planning, verifying and enforcing). For example, the “Compliance” section had a sub-category called “Plan Compliance Verification”, which included a list of all the relevant guidance on this topic and appropriate e-Access links. The repository was also integrated with e-Access, which ensured that any document modifications in e-Access were automatically updated in the repository.

Other strengths noted by DPRR personnel included the use of Power BI charts to visualize work progression, and the use of CMS as a repository for inspection information and related data. However, although CMS was designed as a workflow tool, it did not serve as such. All of the information was typically added after an inspection was completed. There were also some concerns about the future of CMS and potential compatibility issues with future IT systems.

Interviews with DPRR personnel also highlighted inconsistencies and duplication in the use of some IM tools by RPOs across divisions. For example, RIB was used by RPOs to track compliance actions from inspections, correspondence and default compliance assessments. JMS was also identified as a tool used by RPOs to occasionally track compliance actions from inspections if the specialist groups they are collaborating with still use it in their respective divisions. This has led to duplication of work from copying and pasting action items from RIB into JMS. According to management, this duplication may be attributed to interaction with SME groups, not DPRR. It was also noted that Power BI may not be used consistently by RPOs. Some RPOs use Power BI to analyze data for integrated assessments, while some do not. Additionally, there were various ways correspondence from the licensees was tracked among divisions, including the use of a spreadsheet, RIB and MS To Do. Management has indicated that development of a tool is a high priority for DPRR; in the interim, some divisions are experimenting with various IT applications.

Based on the audit testing of completed DPRR inspections, the engagement team determined that key inspection files were well documented, accessible, accurate and consistent among the various tools used, including CMS, e-Access and RIB. Applicable supporting documentation such as inspection plans, records of observations, inspection reports, memos and cover letters were completed, saved and accessible. The lessons learned template was also systematically completed and saved. Moreover, action items from inspections were entered and tracked in RIB as required.

Overall, the general consensus among DPRR personnel was that the IM tools met their needs, which is consistent with the audit testing results. The IM tools were also outdated and inefficient owing to factors such as lack of integration, limited searching and sorting functionality, and inability to generate reports and trends. The lack of integration created manual work and duplication of effort from having to copy and paste the same data in several different tools. Given the lack of integration, data validation and monitoring are key to ensuring data integrity.

The integration of compliance verification information was identified as a recommendation in the 2022 OAG performance audit, Management of Low and Intermediate Level Radioactive Waste. The corresponding management action plan (MAP) assigned to DNCFR included a commitment to establish data management practices, including a data governance framework to support integrated management of compliance data, as well as a review of existing tools to identify potential areas for improvement. The MAP also included a long-term action to assess an integrated system approach to accurately capture and manage the information, understand the effectiveness of the compliance processes, and improve them as required. It is expected that the completion of the above-noted MAP, and the CNSC Digital Strategy, currently in its implementation phase, will help streamline information management, reporting, and data processing going forward.

The integration of IM tools for compliance verification activities was also identified as an opportunity for improvement in the IAEED’s joint audit and evaluation report on DNCFR’s risk-informed compliance verification processes. This presents an opportunity for the ROB directorates to collaborate when working with the Information Management and Technology Directorate (IMTD) to better integrate compliance verification information and processes.

6.4.2. Information Management Tools in Other Organizations

The benchmarking exercise identified 4 organizations with an efficient and integrated software system for IM purposes (refer to figure 5 below). These benchmarking findings are timely for the CNSC, as the organization is currently implementing Horizon 1 of its Digital Strategy, which aims to enable an agile digital workplace.Footnote 7 This includes the delivery of new task management, document creation and workflow automation capabilities.

Figure 5: Information management by other international nuclear regulators and Canadian federal government departments

- One international nuclear regulator developed its information system as part of a strategy to digitize key tasks, increase the accessibility and visibility of information, and enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of its regulatory team. Inspection data in this system was controlled and aggregated in one place so that inspectors could see trends in compliance. There was also a secure link where licensees could seamlessly upload files for inspectors.

- One international nuclear regulator developed an in-house digital tool to plan, conduct, report on and document its inspection activities. It provided a web-based online tool for concurrent input by multiple inspectors working on a team inspection.

- One Canadian federal department built its information system using an integrated, modularized workflow approach for several activities, including, but not limited to, compliance verification, remediation and other enforcement activities. The information system supported planning, conditional oversight and data analysis.

- One Canadian federal department developed an in-house information management tool that supported risk assessment activities, compliance and related information tracking.

6.4.3. Collaboration and Knowledge Management

Collaboration among DPRR personnel and SMEs is embedded in core DPRR processes such as the development of the annual compliance verification plan and the conduct of inspections and compliance assessments. Collaboration has been further formalized and encouraged through the production of documents, such as DPRR Principles of Multi-Key Approach Footnote 8 to Decision-Making, which delineate roles and responsibilities between DPRR and TSB staff. The sharing of lessons learned from compliance verification activities has been identified as a key collaboration activity. According to DPRR personnel, lessons learned are exchanged at different levels, including, but not limited to, various meetings for directors, inspectors and RPOs; monthly workshops; and bi-weekly OPEX Footnote 9 meetings. Additionally, PRLCID facilitates regular meetings summarizing lessons learned entries from CMS. Collaboration also takes place through informal communication channels, such as mentorship and Teams chats, which are important means for collaboration.

Principles of knowledge management (KM) have been formalized within DPRR in thedocument Information Report: Knowledge Management for an Effective NPP Regulator. The report describes key practices to promote KM, such as staff training, sharing of lessons learned, and implementing a system of governance documents to reflect best practices and to promote consistency. The engagement team determined that such practices are in place within DPRR.

The general consensus among RPD directors, PRSIs and RPOs was that KM practices and collaboration with SMEs is effective for DPRR's risk-informed compliance verification activities. Interviews demonstrated mixed opinions among RPOs pertaining to the quality of collaboration within the RPO community. Some RPOs noted effective collaboration with RPOs in other divisions that are responsible for similar SCAs, while others suggested that the consistency of collaboration across all SCAs needs improvement. There is an opportunity to explore this topic further by engaging with RPOs through various channels, such as the RPO forum, to ensure that RPOs from all divisions are able to leverage the benefits of collaboration.

6.4.4. Conclusion

Overall, the use of IM tools across DPRR was generally consistent, and information was accessible, reliable and accurate. Knowledge management has been formalized within DPRR and was practiced in areas such as staff training, governance documentation and the sharing of lessons learned. Collaboration among DPRR and key stakeholders was effective, and multiple channels were established to foster these connections. There is an opportunity to enhance collaboration among the RPO community.

Some duplicative efforts and documentation inconsistencies were identified, particularly with information in RIB and JMS. If IM tools are not used in a consistent manner and information is spread across a variety of platforms, inefficiencies or errors in the compliance verification process may result. This could lead to more duplicative efforts, leaving less time for other compliance verification activities.

It would be advantageous for the CNSC to consider the IM best practices identified in this report and the feedback from DPRR staff when implementing the CNSC Digital Strategy initiatives.

Recommendation

- DPRR should ensure that information management practices are consistent across divisions.

6.5 Effectiveness – Performance Measurement, Monitoring and Reporting

Performance measurement is a systematic approach used to assess the efficiency and effectiveness of projects, programs and initiatives in an organization to ensure that desired outcomes are achieved Footnote 10. The engagement expected to find appropriate performance measures linked to planned results that are continuously monitored and periodically reported on.

Key findings

The engagement found that the performance of DPRR’s compliance verification activities is consistently monitored against planned results and periodically reported to management with an adequate process to manage the performance data related to activities.

DPRR has a high completion rate for the inspections it plans and mostly meets its other performance targets. The performance indicators are risk-oriented and align with those measured at other international nuclear regulators. To improve its coverage, DPRR should consider measuring the percentage of baseline CNSC-initiated compliance assessments completed.

It appears that the CNSC’s compliance verification activities have a positive influence on the safety culture of licensees, and inspections are perceived as value-added activities. Licensees agree that the CNSC’s compliance activities are a driver for continuous improvement, and the CNSC’s processes are mostly understood among licensees. There are opportunities for improvement identified by licensees that are worth exploring further, such as revisiting the compliance assessment process.

6.5.1. Evidence of Performance Metrics

The documentation review and interviews demonstrated that an adequate process was in place to store, collect and analyze DPRR performance data on inspections. This process tracks activities throughout the year and takes a collaborative approach, involving the DPRR Monitoring Officer and stakeholders from the Strategic Planning Directorate (SPD), which is situated within the Regulatory Affairs Branch (RAB). Current limitations pertain to manual efforts and a lack of modern tools, which should be addressed through the implementation of the CNSC’s Digital Strategy. It was evident from stakeholder interviews that this process was well understood by staff. The performance of DPRR’s compliance verification activities was consistently documented, monitored against plan and reported to the Management Committee.

Performance indicators for DPRR’s risk-informed compliance verification activities were clearly defined, documented and aligned with the planned results established for the Nuclear Reactors Program. Stakeholder perceptions on the validity and usefulness of the current performance indicators suggested that indicators are useful for decision making, specifically in terms of adjusting the timing of the inspection plan and providing a good sense of licensee performance. The performance information profile (PIP) for the Nuclear Reactors Program consisted of 4 performance indicators pertaining to DPRR’s compliance verification activities:

- Number of high and medium compliance verification findings for all NPPs

- Number of events and unplanned situations for operating NPPs found to be related to deficiencies in regulatory requirements or practices

- Number of events and unplanned situations at NPPs

- Percentage of baseline compliance verifications activities completed

The percentage of baseline compliance verification activities completed was presented to the Management Committee every quarter; this data focused on inspections. Within DPRR, all compliance verification activities, including status updates on inspections and CNSC-initiated compliance assessments, were monitored and presented every quarter as part of the quarterly review and at integration meetings attended by directors throughout ROB and TSB. The three other indicators were embedded in the annual Regulatory Oversight Report for Canadian Nuclear Power Generating Sites.

The performance indicators highlighting the number of events and unplanned situations at NPPs focused on the results of compliance verification activities, including inspections, CNSC-initiated compliance assessments, and surveillance and monitoring. The performance indicator for the percentage of baseline compliance verification activities completed focused on inspections. While that is essential, it is also prudent to include CNSC-initiated compliance assessments, as they are part of DPRR’s 5-year baseline compliance verification plan. Furthermore, compliance assessments were identified as an area for improvement in the DPRR licensee survey owing to a lack of clarity and perceived inefficiencies (see section 6.5.3). Therefore, it may be beneficial to include CNSC-initiated compliance assessments in the existing indicator on the percentage of baseline compliance verification activities completed. This may help to assess efficiency, support future planning, and identify areas for improvement.

In December 2024, the engagement team observed DPRR’s compliance verification dashboard and noted discrepancies in the number of scheduled CNSC-initiated compliance assessments compared to the data in the 5-year baseline CVP. For example, the dashboard displayed no scheduled CNSC-initiated compliance assessments for the Darlington Regulatory Program Division in fiscal year 2023–24, while the 5-year baseline CVP indicated 8 such assessments. A similar discrepancy was observed for the Point Lepreau Regulatory Program Division. To ensure that the monitoring of compliance assessments is effective, it is imperative that the data from the dashboard and the 5-year baseline CVP be reviewed and reconciled. Management has confirmed that the dashboard was subsequently updated with complete and accurate data.

Specific metrics on equity, diversity and inclusion were not captured in DPRR’s performance indicators, and it was noted during interviews that there was limited awareness on how Gender-based Analysis Plus Footnote 11 (GBA Plus) relates to compliance verification programs. This is consistent with what was identified in Phase I of the IAEED’s joint audit and evaluation of the CNSC’s risk-informed compliance verification processes for DNCFR. The engagement team anticipated a limited awareness across directorates, as the CNSC’s GBA Plus Responsibility Centre currently has limited capacity to proactively engage with the organization on GBA Plus. While there is no evidence that this has negatively impacted staff or licensees, there is an opportunity to ensure that GBA Plus factors are formally considered during the CNSC’s compliance verification activities, such as by reviewing DPRR tools, templates and communication products for gendered language. Incorporating such practices may also help to ensure that the CNSC is meeting mandatory federal GBA Plus requirements. To ensure consistency and prevent duplicative efforts between directorates, it is worthwhile to consider one branch-level approach to the above-noted efforts. These efforts should be conducted in consultation with the Corporate Planning Division, which falls under SPD within RAB. It is the CNSC’s GBA Plus Responsibility Centre and, as such, reports on GBA Plus in the Departmental Plan and Departmental Results Report as required by the Treasury Board. According to Women and Gender Equality Canada, the role of a GBA Plus Responsibility Centre is to lead, support and monitor implementation of a GBA Plus framework, and to provide oversight, direction and promotion of GBA Plus across an organization. However, responsibility for GBA Plus extends across the entire organization and to all individuals, from the senior managers who endorse the policy or statement of intent, to the subject-matter experts, who are best positioned to apply GBA Plus to specific issues.

6.5.2. Achievement of Performance Activity Measures

The benchmarking exercise conducted with 4 international nuclear regulators revealed some good practices pertaining to performance measurement, which DPRR has already adopted. Three regulators had performance measurement frameworks that were outcome-based and grounded in licensee performance. Two regulators assessed overall licensee performance quarterly, with a detailed assessment in the fourth quarter for the fiscal year. The performance results were reported publicly. Another regulator established performance indicators that directly linked back to its strategy and were reviewed quarterly to determine whether the organization was making progress in ensuring that licensees achieve routine compliance. Figure 6 provides an example.

Figure 6: Performance measurement findings from international nuclear regulators

-

One regulator defined performance indicators that linked back to its corporate plan using 5 strategic themes. Compliance inspection activities fell under the theme of “Influencing Proportionate Improvements”. There were 4 performance measures under this theme:

- Regulatory activity drives demonstrable improvements and compliance across purposes.

- Regulatory decisions are proportionate, balanced and unbiased.

- A continuous self-improvement and learning culture.

- Innovators are confident to test and deploy technology in a regulatory framework that embraces innovation.

- Performance was reported publicly in an annual report.

Additionally, one regulator identified risk-oriented key performance indicators covering a range of areas, captured in figure 7 below. These were similar in nature to DPRR’s performance indicators, which suggests that DPRR’s performance measurement practices are well-aligned with international counterparts.

Figure 7: Risk-oriented key performance metrics identified by one international nuclear regulator

- Number of significant events/incidents

- Number of findings above a “low safety and security significance”

- Number of deviations between the situation observed during the inspection and the regulations

- Number of anomalies or aspects warranting additional justifications

- Days lost due to work-related accidents

- Number or rate of safety rule errors

- Number of nuclear security incidents

- Number of regulatory issues

6.5.3. Achievement of Performance Activity Measures

Overall, DPRR’s planned compliance verification inspections were being achieved and measured as demonstrated in the CNSC’s Corporate Performance Report and in annual SPD reporting data. For example, the target for DPRR inspection plan completion is 95%, which has been achieved consistently since fiscal year 2022–23.

The other performance indicators pertained to findings and events at NPPs, such as the number of high and medium compliance verification findings for all NPPs, and the number of events and unplanned situations. Results of these performance indicators are illustrated in figures 8 to 10 below. The performance indicators in figures 8 and 10 reflect the performance of the nuclear industry.

Figure 8: Number of high and medium compliance verification findings for all NPPs

| Fiscal year | # of high and medium findings | Target of a stable or decreasing trend has been met |

|---|---|---|

| 2023–24 | 1 | Yes – Number has decreased since FY 2022–23 |

| 2022–23 | 4 | No – Number has increased since FY 2021–22 |

Figure 9: Number of events and unplanned situations for operating NPPs found to be related deficiencies in regulatory requirements or practices

| Fiscal year | # of events and unplanned situations | Target of 0 met |

|---|---|---|

| 2023–24 | 0 | Yes |

| 2022–23 | 0 | Yes |

Figure 10: Number of events and unplanned situations at NPPs

| Fiscal year | # of events and unplanned situations | Target of a decreasing trend met |

|---|---|---|

| 2023–24 | 11 | No – Number has increased since FY 2022–23 |

| 2022–23 | 6 | No – Number has increased since FY 2021–22 |

6.5.4. Program Effectiveness

The engagement found that the majority of DPRR licensees agree that regulatory requirements are clear, and all licensees perceive inspections as value-added activities. DPRR licensees mostly understood CNSC processes for executing compliance verification activities, and some licensees viewed them as extremely influential to the safety culture of their organization. Some opportunities for improvement were identified by licensees pertaining to the interpretation of regulatory documents among CNSC staff, clarity of compliance assessments, and notification of the compliance verification schedule.

In November 2024, the engagement team issued a survey to all 4 organizations (licensees) overseen by DPRR to evaluate the overall effectiveness of the CNSC’s compliance verification program. Three organizations responded to the survey. One licensee submitted a combined response for 2 of the sites that were invited to participate, resulting in a response rate of 100%. The survey explored perceptions on various topics, including clarity of regulatory requirements and CNSC processes, the CNSC’s risk-informed approach, the usefulness and impact of compliance verification activities, how regulated parties have adopted a safety culture, and areas for improvement.

Clarity of regulatory requirements and CNSC processes

According to the DPRR PIP, one of its intended outcomes is that stakeholders understand regulatory requirements. The understanding of regulatory requirements is critical for delivering on the CNSC’s mandate to regulate the use of nuclear energy and materials to protect health, safety, security and the environment. According to the licensee survey results, 2 out of 3 licensees mostly agree that requirements are clear, and 1 slightly disagrees. Feedback from the licensee that slightly disagreed suggests that regulations and regulatory documents are not prescriptive enough and are therefore open to interpretation. It was indicated that interpretations change from one CNSC inspector to another, making it difficult to comply. Similar feedback was communicated in stakeholder interviews with DPRR personnel. It was noted that there were inconsistencies across sites for how findings are written and how compliance is verified. There is an opportunity for DPRR to strengthen consistency in how the regulatory requirements are verified across the sites, and to target communications to stakeholders so that all licensees can “completely agree” that requirements under their licensee agreement are clear.

For the most part, DPRR licensees understood the CNSC’s processes for executing annual compliance verification plans, as noted in figure 11. The exception pertains to compliance assessments. All licensees indicated that these processes are only slightly understood and suggested that because compliance assessments are a newer tool, there was not a shared understanding between inspectors and what licensees were told by Ottawa program staff. There was also a lack of clarity on how compliance assessments are to be supported in comparison to Type I and Type II inspections. The perception among some licensees is that compliance assessments were implemented to be a less cumbersome process than Type II inspections, which according to licensees is not the case. Licensees noted that it is not typical to see the results from compliance assessments unless there are findings, which adds to their uncertainty. Management has expressed that CNSC-compliance assessments were adopted to help reduce the administrative burden and formal process of a Type II inspection. As a result, no report is circulated to licensees, as they are not intended to receive the results of the assessment. Based on the results of the licensee survey, this context is not entirely understood by licensees. Desktop assessments were slightly less understood than other compliance tools as the licensee is not generally involved.

Figure 11: Understanding of the processes undertaken by the CNSC during the execution of its annual compliance verification plan

| CNSC process | Process is not understood | Process is slightly understood | Process is somewhat understood | Process is mostly understood |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Field inspection | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Type I inspection | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Type II inspection | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Desktop inspection | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Compliance assessment | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

Safety culture

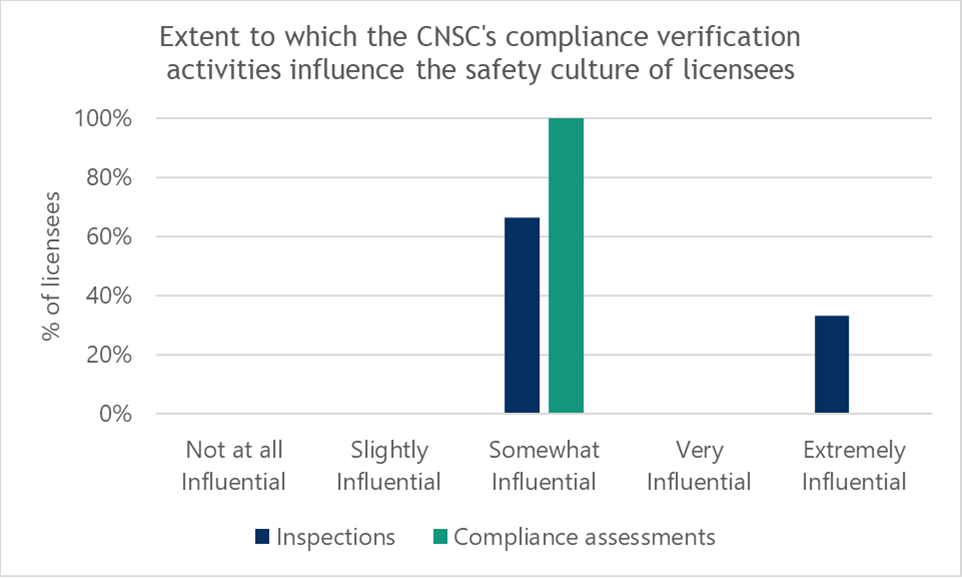

Some licensees Footnote 12 indicated that the CNSC’s compliance inspection activities were extremely influential to their organization’s safety culture, while the majority indicated that these activities were somewhat influential (see figure 12). All licensees rated the maturity of their safety culture to be very high, at a level of optimization where their focus is on continuous improvement. The mature capacity of the operators may explain the positive, but moderate, perception of the contribution of CNSC compliance verification activities to licensee safety culture. Collectively, open-ended responses indicated that licensees view CNSC compliance activities as a driver for continuous improvement, where they can learn from findings and implement corrective action processes.

Figure 12: Extent to which the CNSC's compliance verification activities influence the safety culture of licensees

Text description of figure 12

Extent to which the CNSC’s compliance verification activies influence the safety culture of licensees

| Not at all Influential | Slightly Influential | Somewhat Influential | Very Influential | Extremely Influential | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inspections | 0% | 0% | 67% | 0% | |

| Compliance assessments | 0% | 0% | 100% | 0% | 0% |

The CNSC’s risk-informed approach and overall effectiveness

There was a mixed response related to the extent to which the CNSC applies a risk-informed approach in the selection and conduct of its compliance verification activities. Two of the 3 licensees mostly agreed with this statement.